Hawaii, Honolulu

The potential for trade via Pacific Ocean routes had interested the United States ever since the 1780s. Americans had traversed it as fishermen, whalers, traders, navigators, and also missionaries, who established congregations and promulgated Christianity wherever they settled. The Hawaiian Kingdom had graciously accommodated this influx of foreign settlers, all of whom planted the islands with the seeds of mainland culture in the forms of schools, churches, businesses, and farms.

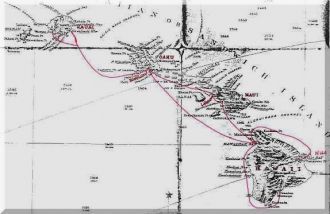

American farmers were particularly intrigued by the seemingly effortless production of sugar in Hawaii and sought to purchase lands for plantation. To their advantage, in 1875 the United States established an important economic tie with Hawaii in allowing its sugar to be sold within the States duty free. This trade policy was a boon to sugar producers and also served to economically bind Hawaii to the States. In return, in 1877 the Hawaiian Kingdom, the islands' ruling monarchy, granted the United States the exclusive right to use Pearl Harbor.

In 1890, however, American tariff laws were again changed, this time in favor of domestic sugar suppliers. At that time, farmers of American descent owned two-thirds of the land of the Hawaiian Islands. Attempting to regain lost markets, the planters sought to sidestep American trade policy by lobbying for the annexation of Hawaii to the country.

Compounding their frustration, in 1891 Queen Liliuokalani, who saw herself as a protector of the region's culture and politics, ascended the Hawaiian throne. Born in Honolulu to the high chief Kapaakea and his wife the chiefess Keohokalole, Liliuokalani was the third of ten children; her brother, Kalakaua, was the King. In January, 1891, after her brother's death, Liliuokalani ascended the throne. The new Queen resented the encroachment of American culture and religion, and she also disliked their capitalistic interest in her Kingdom's natural resources and politics. Hoping to preserve the ancient culture of her islands, the Queen renounced the "Bayonet Constitution" of 1887, which had been put in place by the American colonists. The document limited both the power of the monarch and also the political power of native Hawaiians. In renouncing this set of bylaws, she limited the involvement of foreigners in island politics while preserving her own position as sovereign ruler with all accompanying legislative powers.

This turn of events enraged American agriculturalists, whose economic positions would inevitably falter under monarchial leadership. The American minister to Hawaii, John Stevens, devised a bloodless coup, which was carried out by one hundred fifty marines stationed on the USS Boston in nearby Pearl Harbor. Queen Liliuokalani was removed from her governing seat, and two weeks later Stevens announced Hawaii a United States protectorate. He recommended to Congress that the islands be annexed as a territory, stating, "The Hawaiian pear is now fully ripe, and this is the golden hour for the United States to pluck it." Although this suggestion was rejected on multiple occasions by the Senate and then by President Cleveland, in 1898 Hawaii was annexed as a United States territory. Sixty years later in 1959, it became the country's fiftieth state.

Peattie did not condone Queen Liliuokalani's removal from office and wrote several editorials on the subject. To make matters worse, one year after the Queen was dethroned, the United States military stormed her place of residence and found a small number of weapons in the garden. Although Liliuokalani claimed that she had not had any knowledge of the tiny cache, she was fined and imprisoned by American authorities. In 1895 Peattie penned with more than a little indignation, "Five years in prison! Five thousand dollars fine! That is the price one woman is sentenced to pay–for what? For being suspected of trying to regain what is right by her own . . . when a thing of that sort is done to an innocent woman, other women are inclined to ask why."

The manner in which the Queen's residence was searched by the military also offended Peattie. In the World-Herald she quoted a Hawaiian periodical, The Advertiser, that had run a description of the raid: "Her home was searched for ammunition and arms, and a small among of both were found in her cellar. There were also some bombs made of coconuts and other things, and which "wore a very wicked look," so the local paper states." Peattie likened the United States' imperialistic actions in Hawaii to the "hypocritical and arrogant attitude" the country had taken when claiming the lands of the American Indians. The government's attitude to the Indians had not precluded them from "defrauding them, lying to them, confining them within bounds as if they were cattle, forbidding them to sell their possessions except to us . . . disregarding their tribal government . . . " Queen Liliuokalani's predicament also paralleled the New Woman's struggle for equal rights. "The provisional government has seemed to some persons a far more treasonable thing than poor Liliukalani's struggle for her rights could possibly do." From confinement, Queen Liliuokalani had written a letter to the public, describing the "rightness" of her actions, which had all been formulated and carried out in accordance with the consent of her advisory cabinet. Peattie was obviously moved by the royal woman's epistle, for she quoted it in full in her column.

Almost one hundred years after Peattie's editorials ran in November 1993, President Bill Clinton would sign United States Public Law 103-105, acknowledging the 100th year anniversary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy of Hawaii and Queen Liliuokalani. The bill would also apologize for the United States' hasty overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Source: http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/peattie/ep.owh.pol.0004.html

USA,

USA,