USA, New York City

ONE hundred years ago, the crossing of Broadway and Seventh Avenue was a drabble of cheap hotels, some doubling as brothels, and a collection of dealers in harnesses and carriages. It took the name of a similar quarter in London, Longacre Square, and it was a muddy endpoint to the dazzle of the Gay White Way that bathed Broadway in a glitter of theaters and restaurants from Union Square up to, but not including, 42d Street.

But on Nov. 25, 1895, the square's future was transformed with the magic twinkle of the grand, three-hall Olympia Theater, on the east side of Broadway between 44th and 45th Streets. The opening capped more than a century of theater's sprint up Broadway.

The date this year is more of a 100th wedding anniversary than a birthday, the union of show business with the neighborhood that to this day is its main stem -- renamed Times Square nine years after the Olympia opened, thanks to the presence of the newspaper that has been its occupant ever since and to the opening of a subway station. The matchmaker for that union was a visionary named Oscar Hammerstein.

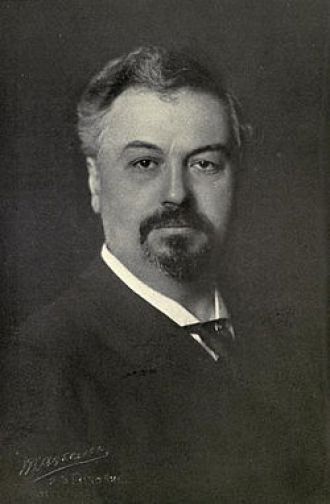

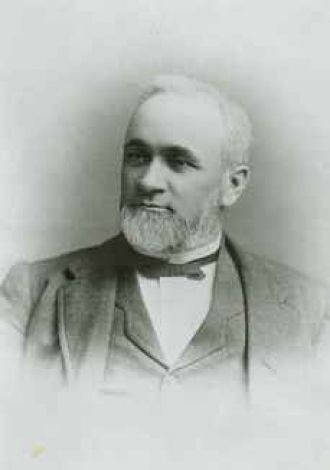

Hammerstein arrived as a German Jewish teen-ager and worked his way up in the tobacco business, in which he majored and prospered, and began a lifelong romance with theater, in which he minored, financially speaking, and often went broke.

He was a colorful figure, designated by later generations Oscar Hammerstein 1st, to distinguish him from his grandson Oscar Hammerstein 2d. Oscar 2d was the lyricist who, following in the footlights of his forebear, added to the luminosity of Times Square with successes like "Show Boat," "The Sound of Music," "The King and I," "South Pacific" and "Oklahoma!"

Oscar 1st owed a lot to cigars. He made them, and smoked them, and held patents on 50 cigar machines. The tobacco money, and Oscar's daring, enabled him to buy the Longacre property and erect the Olympia, a massive building of gray Indiana limestone designed in French Renaissance style, with a ventilating system for heating and cooling, and lighting by four dynamos that provided 3,200 amperes of current.

The opening was stupendous. The New York Times's front page the morning after reported that Hammerstein had to call on the police to help him keep people out of the new theater, "one of the most colossal places of amusement in the world." He had seating room for 6,000; he sold 10,000 tickets. The play was the premiere of "Edward E. Rice's Excelsior, Jr.," a comic opera.

Crowds also surged into the Olympia's music hall, which featured 30 European entertainers with marionettes, somersaulters, high-wire walkers, clowns and a female impersonator. The run-over crowd took refuge in the concert hall, where a band played on until 1 A.M. But thousands were turned back into the mud and slush of Longacre. As the night wore on, the situation worsened, The Times reported, and the restraining tactics shifted from medieval warfare to those of the modern gridiron, with nobody to retire the injured from the field or to count the yards of gain or loss.

Hammerstein's thrust into the square was bold, but perhaps not as revolutionary a leap as he had taken in 1889, when he opened the Harlem Opera House and the Columbus Theater on 125th Street. His theatrical gambles were often tinged with real-estate speculation: in this case, he thought the theaters might attract upwardly mobile families to the virtually uninhabited neighborhood.

Hammerstein, an incurably optimistic impresario and real estate investor, enjoyed pioneering. His great-grandson Oscar 3d, who has been researching his ancestor's life for a book, ticked off, in an interview, the theater-builder's ups and downs.

"Oscar went broke on the Olympia, which I think had too many seats for that time," said Mr. Hammerstein, 39, the son of Oscar 2d's son James. The theater opened just before the flowering of vaudeville, which he relates to waves of immigrants who did not understand English well enough to sustain theaters. So Oscar 1st, who kept opening theaters, kept going broke. "If he had opened the Olympia, say, in 1915," Mr. Hammerstein said, "it would have been a success."

By 1898, Oscar 1st had lost the (still uncompleted) Olympia. It became two theaters; one, the Criterion, turned into a movie house, and the entire building was finally demolished in 1935. But Oscar's luck was better than the Olympia's. Without financial reserves, he somehow managed to line 42d Street with theaters: the Victoria in 1898, the Republic in 1899, the Lew Fields in 1904.

If Hammerstein was not a Diamond Jim Brady, he was a pioneer. He brought the theater into the square; the theater brought the movie palaces, the restaurants, the cheap and flashy, the vulgar and tawdry, cheek by jowl with the expensive and swellegant entertainments and the big, bright display signs that have constituted an electrifying light extravaganza.

Times Square is as influential a center of culture as can be found in America, with the conspicuous exception of Hollywood, yet it's 100th anniversary does not inspire solemnity, nor should it. The square's reputation is as X-rated as its X-shape. It embraces the highest level of theatrical art and the lowest level of pornography, sprinkled with movie houses of every pretension in between.

The cable cars and hansoms no longer deposit their fares in slush and mud as they did on the Olympia's opening night. But Oscar would find that, when the show lets out, it is still no easier to find a cab.

Starting in the 18th century, theaters slowly climbed up Broadway until they reached and began collecting in what we now know as Times Square. here is a sample of the historical trail.

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/05/nyregion/looking-back-hammerstein-s-gamble.html

USA, New York City

USA, New York City