Scotland,

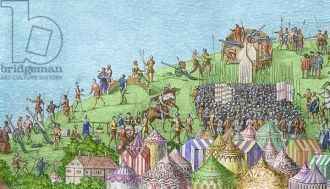

Centuries of military struggle between Scotland and England have produced some epic contests, still seared into the folk memory of the two countries, from the humbling of English knighthood at the spear points of doughty Scots commoners at Bannockburn in 1314 to the death of Scotland’s impetuous but chivalrous King James IV at Flodden in 1513. Among the multitude of other famous battles is one whose name is less readily recalled, fought outside Musselburgh on September 10, 1547.

Perhaps one reason why the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh (cleugh being a narrow glen or valley in Scots-Gaelic) has been all but forgotten is because its political consequences were so slight. England’s ambitious Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, had come to Scotland to win a bride, at the point of a sword, for his young master, the 9-year-old King Edward VI. In that, however, he would fail–Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, was spirited away to France, dashing English hopes of a union of the two crowns.

Yet, in one respect, the battle was highly significant.

Historians have tended to regard the British Isles as a military backwater in the 16th century, but a close examination of the campaign suggests that Pinkie Cleugh was the first ‘modern’ battle on British soil–featuring combined arms, cooperation between infantry, artillery and cavalry and, most remarkably, a naval bombardment in support of land forces. Such an interpretation places "Britain" in the mainstream of military development 100 years earlier than is generally accepted.

Upon his death in January 1547, the megalomaniac English King Henry VIII had bequeathed to his nation an ongoing war with Scotland. His major diplomatic ambitions had been in continental Europe, but securing the volatile northern border with Scotland was an essential prerequisite for campaigning in France. The ideal solution to Henry’s problem would have been a union of the two crowns through the marriage of his young son, Edward, to the infant Mary, Queen of Scots. Certainly, in that time of political and religious upheaval there were many Scottish nobles who were not unreceptive to the idea. However, Henry’s approach to courtship–the ‘rough wooing’ that saw English armies rampage throughout the border country, behaving with the utmost brutality in an attempt to intimidate Scotland into acquiescence–drove many potential allies into the pro-French camp.

After Henry’s death, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Protector of England as regent to the child King Edward VI, devised a new strategy to win the ‘bride’ for his master. He hoped to not only successfully invade Scotland but also establish permanent garrisons in strategic positions across the country, holding it in virtual subjugation.

William Patten, secretary to the English commander, wrote an eyewitness account of Somerset’s campaign, The Expedition Into Scotland, 1547, in January of 1548, while events were still fresh in his mind. In marked contrast to the vague accounts by monastic chroniclers, 16th-century record-keepers like Patten left behind more detailed accounts, which make it clear that Renaissance battles were more sophisticated than their medieval predecessors. Patten describes a campaign that would not seem unfamiliar to a student of the Napoleonic wars.

The 16th century was a transitional period in the European ‘art of war.’ In the course of the so-called Great Italian Wars, triggered by French King Charles VIII’s invasion of Italy in 1494, the weapons and tactics of medieval warfare were gradually supplanted by new methods, involving the operation of cavalry, artillery and infantry arms in an increasingly complex tactical synthesis. Vast phalanxes of well-drilled pikemen and missile troops armed with the harquebus (a matchlock firearm fired from a portable support) and later the musket maneuvered on the battlefields of Cerignola (1503), Ravenna (1512) and Pavia (1525). Light cavalry, notably mercenary Albanian stradiots, Spanish genitors and German Reiters, developed an increasingly important independent role. Men-at-arms, heavy cavalry still armored from head to toe, enjoyed a renaissance of their own, back in the saddle after the decline of the ‘English’ tactic of dismounted fighting. The most potent heavy cavalry was the French Compagnie d’Ordonnance, a permanent professional force employed directly by the state.

The British Isles, locked in internecine conflicts in the latter half of the 15th century, were apparently on the peripheries of the military revolution. England’s armies generally clung to the old dismounted ‘bill and bow’ formations that had worked so well at Agincourt in 1415. Scotland, threatened by a powerful and aggressive neighbor, relied on peasant levies armed with bow, spear and two-handed sword for defense. The Wars of the Roses, however, had not entirely isolated England from developments on the Continent. Foreign mercenaries had brought pikes and handguns to English battlefields (with little success against native bows and bills), and English men-at-arms, despite their traditions of dismounted combat, had fought once more from the saddle to play a decisive part in the Yorkist victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471.

Light cavalry–referred to as ‘prickers’ by the Yorkists–had also played a vital role for the rival armies, gathering intelligence, carrying out feints, and skirmishing with their enemy counterparts. The cream of English light cavalry were Northerners–reivers from the volatile Anglo-Scots frontier who served in all of King Henry VIII’s campaigns in France.

English infantry, too, had not been untouched by modern developments. Under Henry VIII, the English had experimented widely with gunpowder weapons, particularly for naval use, as the ordnance recovered from the sunken warship Mary Rose has indicated. In terms of ‘professionalization,’ England maintained small numbers of garrison troops in the Calais Pale and at Berwick, but Henry’s most important standing units were afloat. According to the Calendar of Scottish Papers, 1, 154763, the armada that accompanied England’s land forces northward in 1547 was crewed by 9,222 mariner-soldiers. Those men, along with the men-at-arms and ‘Gentlemen Pensioners’ of the Royal Bodyguard, are an indication that Henry took greater steps to create large-scale, standing forces than has been recognized in the past.

One important feature of the military revolution was the increased size of armies. To fill out their armies, princes competed for the services of large bodies of international mercenaries, the most highly prized of which were Swiss and German (Landsknecht) pikemen. The 42,000 men amassed by Henry VIII in 1544 for his so-called Enterprise of Boulogne included 4,836 foreign horse and 5,392 foreign infantry. The 16,000-man army that Somerset would lead across the Tweed River into Scotland in 1547 also contained a significant proportion of foreign specialists, most notably a complement of mounted harquebusiers under a Spanish captain, Sir Pedro de Gamboa.

While some English equipment was archaic, more modern technology was also employed, including an impressively large artillery train, under a master gunner appointed directly by the king. Under Henry VIII’s enthusiastic patronage, artillery tactics had become surprisingly sophisticated. At Pinkie Cleugh, the guns accompanying the army would be manhandled into action speedily and with devastating effect. The warships of Somerset’s accompanying naval force, commanded by Lord Edward Clinton, were very effective floating gun platforms, capable of battering enemy ships into submission, or sinking them, with long-range gunfire rather than by ramming or boarding, as had been the traditional practice. From positions in the Firth of Forth, they would support the English land forces at Pinkie with a timely and effective shore bombardment.

Despite the oft-quoted view of the English as primarily infantry oriented, Somerset had amassed some 4,000 cavalry, under the overall command of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick and Duke of Northumberland, for his invasion of Scotland. That considerable mounted arm included the light cavalry, Northern Horse and Gamboa’s mounted harquebusiers (’hackbutters’ to the English).Among the heavy cavalry were 500 ‘Bullerners’–men-at-arms from the garrison of Boulogne–the Gentlemen Pensioners of the Royal Bodyguard and a force of ‘demi-lancers.’ The latter were lance-armed cavalry whose horses were unarmored and who had replaced their own leg armor with stout, thigh-length boots, a compromise of protection for increased speed, mobility and flexibility.

On the face of it, the Scottish army still seemed medieval in its organization. Every man was expected to equip himself for war according to his income, from suits of plate armor for the nobility to brigandines for the less exalted. Legislation also specified acceptable weapons–spears, pikes, light axes, halbards, bows, crossbows, handguns and two-handed swords. To check that men met those requirements, ‘wappenschaws,’ or musterings, were held, at which men presented themselves fully equipped.

The Scottish army of the 16th century had few professional soldiers, nor any permanent force comparable with those on the Continent. It was also particularly deficient in cavalry, since the country was economically unable to support a force of heavy cavalry on the Continental model. Scotland had its own border reivers, who harried the English as they moved north, but they were outnumbered by their generally better-equipped English counterparts. The majority of Scots who faced Somerset at Pinkie Cleugh fought on foot, as they had always done.

William Patten’s description of Scottish soldiers at Pinkie indicates that most were equipped with protective brigandines or ‘jacks,’ helmets, targes, pikes and swords of high quality. Alongside the pikemen served the Highlanders, generally less well-armored than the Lowland levies, but formidably armed with longbow, ax, two-handed sword, or with some form of light ax, such as the Jedburgh stave–useful in the confines of a melee or for hooking cavalrymen off their steeds.

The standard Scottish infantry weapon was the pike, a weapon that had come to dominate European battlefields in the late 15th century. Well-drilled Swiss and Landsknecht formations were not only invulnerable to heavy cavalry but, by using rapidly moving mass columns of pikes and halbards, they had transformed themselves into an offensive weapon as well. The English, whose bowmen had scored a rare success against mercenary pikemen at Stoke in 1487, were slow to adopt the pike. But for the Scots, who, like the Swiss, were less intimidated by enemy cavalry than they were by missile weapons, the pike was an ideal weapon with which to rapidly close with and engage English bow and bill formations.

After the Battle of Flodden in 1513, the Bishop of Durham reported that the Scots had advanced ‘in good order, after the Almayne’s [German's] manner.’ An inherent weakness in reliance upon pike columns had already been demonstrated at Cerignola, in 1503, when Swiss pikemen had floundered before Spanish entrenchments, well garnished with cannons and harquebuses. At Marignano in 1515–a battle that was to have distinct echoes at Pinkie–a Swiss pike column was halted by a French cavalry charge, then decimated by artillery fire. Nevertheless, the pike was still formidable against an enemy maneuvering for position.

Scotland had also developed a keen interest in the gunpowder revolution, but an indigenous gun-founding industry was slow to develop and the country remained dependent on foreign imports. Legislation demanded that merchants carry at least two ‘hagbutts’ (harquebuses) and powder on homeward voyages from the European mainland. The Scots chief missle weapon at Pinkie Cleugh remained the bow, but they clearly had enough guns to worry the English. One estimate of 1522 referred to the Duke of Albany’s forces on the border having a ‘marvelous great number of hand gonnes’ and 1,000 arquebus a croc–heavy harquebuses mounted on wagons. Scotland’s commitment to ‘pike and shot’ formations clearly demonstrated that, in terms of tactics and equipment, their army, too was developing on the same lines as other European armies.

The English army crossed the Tweed River into Scotland on September 1, 1547, while its supporting fleet skirted the coastline. Light cavalry preceded the advance, probing cautiously along the route north and skirmishing with their Scottish counterparts. Small garrisons, sometimes comprised of only a handful of men in the path of the invader, resisted until they were overwhelmed. The English made prominent use of their firearms in those skirmishes, including Gamboa’s mounted harquebusiers, who clashed with Scottish light horse outside Dunbar.

The Scottish horse–borderers for the most part, who likely had close kin in the English ranks–shadowed the advancing army. The reivers, whether English or Scots, were dangerous adversaries (indeed, given their unpredictability and uncertain loyalties, it was dangerous even to have them on one’s own side). Somerset’s army now eyed the large bands of Scottish troopers warily.The Scots laid ambushes, tempted the English to break formation and employed cunning ruses de guerre to disrupt the advance, at one point trying to tempt an English galley to come ashore, to what would have been an inhospitable welcome, by waving the Cross of St. George on the shoreline. Their success, however, was limited; the English harquebusiers, both on foot and mounted, kept them at arm’s length.

The English finally drew close to the main body of the Scottish army, which was perhaps 26,000 strong, on September 9. The Scottish commander, James Hamilton, the 2nd Earl of Arran–who, like Somerset for King Edward, was serving as regent for the 5-year-old Queen Mary–had selected a strong position following the line of the river Esk, along Edmonston Edge, between Musselburgh and Inveresk. To their left lay the Firth of Forth, and to their right lay an area of extensive marsh. Before them the ground sloped away, with the Esk flowing along the base of the ridge…

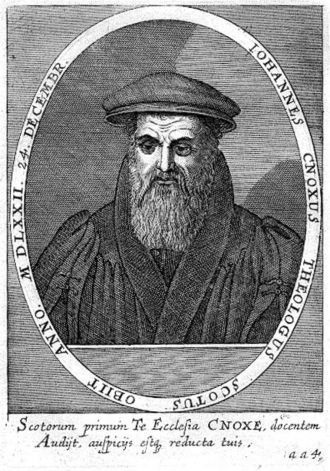

Source: http://www.thesonsofscotland.co.uk/thebattleofpinkie1547.htm

United Kingdom,

United Kingdom,