USA, Ohio

CSX 8888 Runaway Investigation, received by Email on November 5, 2001.

Unmanned Train Movement

In accordance with your instructions, the following report summarizes the work of the investigation committee which was assigned to review and analyze the events of May 15, 2001, in which a locomotive with cars departed from Stanley Yard on the CSXT near Toledo, Ohio and traveled south to Kenton, Ohio, with no crew member on board. I was assisted in this review by MPE Inspector Mike Lusher and OP Inspector Ed Scalzitti, both of whom responded initially to the incident, and by Chief Inspector Harold Rugh, who provided essential technical information.

Synopsis

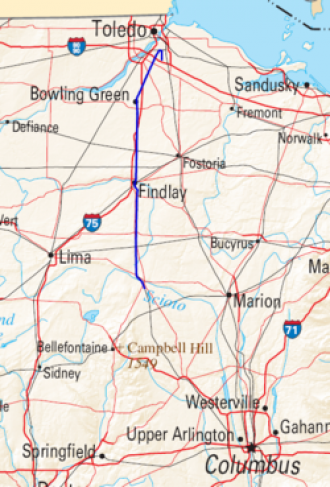

On May 15, 2001, at approximately 12:35 p.m., DST, an unmanned CSX yard train consisting of one model SD-40-2 locomotive, 22 loaded, and 25 empty cars, 2898 gross trailing tons, departed Stanley Yard, which is located in Walbridge, Ohio. The uncontrolled movement proceeded south for a distance of 66 miles before CSX personnel were able to bring the movement under control. At the time of the incident, the weather was cloudy with light rain. The ambient temperature was 55 degrees Fahrenheit. There was no derailment of equipment or collision. There were no reportable injuries as a result of the incident.

Circumstances Prior to Incident

Yard crew Y11615, consisting of one engineer, one conductor and one brakeman, reported for duty at Stanley Yard, Walbridge, Ohio, at 6:30 am, DST, May 15, 2001. After the normal job briefing with the trainmaster, crew Y11615 performed routine switching assignments until approximately 11:30 am, at which time the crew received new instructions and a second job briefing. A few minutes before 12:30 p.m., the crew entered the north end of track K12, located in the classification yard, with the intent to pull 47 cars out of K12 and then place these cars on departure track D10. Locomotive CSX 8888 was positioned with the short hood headed north. The engineer was seated at the controls on the east side of the locomotive.

The locomotive coupled to the 47 cars on track K12, as instructed and planned. The air hoses between the locomotive and the cars were not connected, as is normal during this kind of switching operation. The air brakes on the cars were therefore inoperative. The brakeman notified the engineer by radio to pull north from K12. After the rear or 47th car passed the brakeman's location, he walked west to position the switch for the reverse movement to proceed into the assigned track D10.

The movement continued north out of K12 passing the conductor, who was positioned on the ground at the "Camera" switch. The conductor advised the engineer by radio of the number of cars that had passed him and received an acknowledgement from the engineer by radio.

The Incident

With eight cars remaining to pass over the "Camera" switch, the conductor notified the engineer by radio to prepare to stop. The engineer did not respond to his communication. The conductor again notified the engineer when four cars remained to clear the switch, but again there was no response from the engineer. The conductor then ordered the engineer to stop movement, but again there was no response from the engineer and the movement continued.

In his interview, the engineer stated that as he pulled north out of K12, he was notified by radio by the conductor that the trailing point switch for track PB9 off the lead was reversed. The engineer understood that it would be necessary for the movement to be stopped short of the PB9 switch in order to line the switch for movement further along the lead. Neither the conductor nor the brakeman were near the PB9 switch, and the engineer intended to stop his train, dismount from the locomotive, and align the switch to its normal position, if necessary. The speed of the movement up the lead had now reached 11 mph. The engineer observed the reversed switch, but due to the wet rail conditions and the number of cars coupled to his locomotive, he foresaw that he could not bring the equipment to a stop prior to passing through the misaligned switch.

The engineer responded by applying the locomotive's independent brake to full application. The independent brake applies the brakes on the locomotive but does not apply the brakes on the individual freight cars. In addition, he reduced brake pipe pressure with a 20 psi service application of the automatic brake valve. The automatic brake is pneumatic braking system designed to control the brakes on the entire train. Still certain he would not stop short of the switch the engineer attempted to place the locomotive in dynamic brake mode. The dynamic brake utilizes the locomotive propulsion system to brake the train. Dynamic braking is analogous to down shifting a truck or automobile. Unfortunately, the engineer inadvertently failed to complete the selection process to set up the dynamic brake. Under the mistaken belief that he had properly selected dynamic brake, the engineer moved the throttle into the number 8 position for maximum dynamic braking. The engineer believed that the dynamic brake had been selected and that additional braking would occur. However, since dynamic brake set up had not been established, the placing of the throttle into the number 8 position restored full locomotive power, instead of retarding forward movement of the train.

While the train was still moving at a speed of approximately 8 mph, the engineer dismounted the locomotive and ran ahead to reposition the switch before the train could run through and cause damage to the switch. The engineer was successful in operating the switch just seconds before the train reached it. The engineer than ran along side the locomotive and attempted to reboard. However, the speed of the train had not decreased as the engineer had expected but had increased to approximately 12 mph. Due to poor footing and wet grab handles on the locomotive, the engineer was unable to pull himself up on the locomotives ladder. He dragged along for approximately 80 feet until he released his grip on the hand rails and fell to the ground.

Unable to reboard and stop the movement of his train, the engineer ran to contact a railroad employee, not a member of his crew but in possession of a radio, located at the north end of the yard. This employee immediately notified the yardmaster of the runaway train. The yardmaster promptly notified the Stanley tower block operator and the trainmaster. The Toledo Branch train dispatcher located in Indianapolis was also notified. The movement was now proceeding southward on the Toledo Branch (Great Lakes Division) governed by Traffic Control System (TCS) Rules. The time was approximately 12:35 p.m.

The brakeman observed the train depart the yard but did not initially see the engineer on the ground. The brakeman and another employee used a personal vehicle to pursue the train to the next grade crossing to attempt to board the train. Their immediate concern was for the safety of the engineer, who they feared may have suffered a heart attack while at the controls of the locomotive. At the grade crossing, the two employees were unable to board the train as the speed had increased to approximately 18 mph as it passed the mile post 4. Local authorities and the Ohio State Police were notified of the runaway train at approximately 12:38 p.m.

Attempts to Stop the Runaway

At a siding called Galatea, near mile post 34, at approximately 1:35 p.m., the train dispatcher remotely operated the switch for the train to enter the siding. Previously a portable derail had been placed on the track in an attempt to derail the locomotive and thereby stop the movement. The portable derail was, however, dislodged and thrown from the track by the force of the train passing over it, and the movement of the train was not impeded.

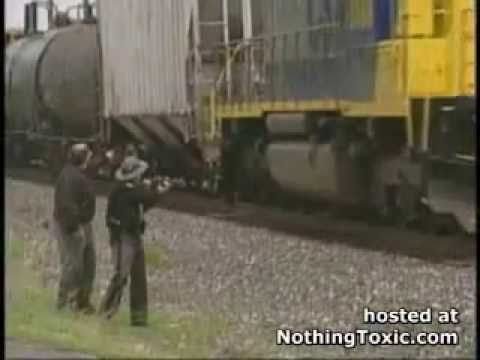

Northbound train Q63615 was directed by the dispatcher into the siding at Dunkirk, Ohio. The crew was instructed to uncouple their single locomotive unit from their train and wait until the runaway passed their location. at approximately 2:05 p.m., the runaway train passed Dunkirk, and the siding was lined for the crew of Q63615 to enter the main track and to pursue the runaway train.

At Kenton, Ohio, near mile post 67, the crew of Q63615 successfully caught the runaway equipment and succeeded in coupling to the rear car, at a speed of 51 mph. The engineer gradually applied the dynamic brake of his locomotive, taking care not to break the train apart. By the time the train passed over Route 31 south of Kenton, the engineer had slowed the speed of the train to approximately 11 mph. Positioned at the crossing was CSX Trainmaster Jon Hosfeld, who was able to run along side the unmanned locomotive and climb aboard. The trainmaster immediately shut down the throttle, and the train quickly came to a stop. The time was 2:30 p.m. and the runaway train had covered 66 miles in just under 2 hours.

An examination of the controls confirmed that the locomotive independent brake had been fully applied, automatic brake valve was in the service zone, and the dynamic brake selector switch was not in the braking mode. All brake shoes had been completely worn to the brake beams.

The railroad was prepared to place an additional fully manned locomotive ahead of the runaway south of Kenton, if necessary, to further slow the train. This rather hazardous option was fortunately not required.

Post Incident Investigation

The engineer of Y11615 was slightly injured, but he declined medical treatment. He was released from service with his crew at 5:30 p.m. The CSX did not require Drug or Alcohol testing of the crew, nor was federal testing required.

The engineer first hired on the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1966, and he was promoted to engine service in 1974. He received his most recent check ride with a supervisor in January 2001. The engineer's discipline record is clean.

A Federal Railroad Administration Motive Power and Equipment Inspector arrived at the location where CSX 8888 was stopped and performed a full mechanical inspection. He found all systems to function normally, including sanders, headlight, auxiliary lights, bell, horn and the alerter. The brake cylinder piston travel could not be determined, because all brake shoes were completely burned off.

Conclusions

Air Brake System

Locomotive CSX 8888 is a model SD-40-2 manufactured by General Motors Corporation (EMD). This unit is equipped with 6L type air brake system. The Alerter system is connected directly to the air brake system which functions to provide an automatic full service penalty application of the air brake system, and a power knock out (PC) caused by failure to acknowledge the time out feature usually about 40 seconds. When the Alerter time out has expired, the engineer must acknowledge by tripping the acknowledging switch which will reset the time out feature. The Alerter system is nullified when locomotive brake cylinder pressure of 20 psi is developed in the Independent Application and Release pipe. This also prevents the P2A Application Valve from triggering a service brake application and PC action.

When the engineer of Y11615 placed the locomotive independent brake valve into full application, a design pressure was developed in the brake cylinders, depending on the type of relay valve, which nullifies the Alerter System. Had the engineer not placed the independent brake into the full applied position and caused a build up of brake cylinder pressure, when the time out feature had expired, the system would have functioned causing not only an application of the locomotive brakes but a PC trip which would have resulted in a Power Knock Out bringing the movement to a stop.

According to the interview of the engineer, he made a 20 psi brake pipe reduction with the automatic brake valve before dismounting the locomotive. This by no means would have provided any braking power in as much as the brake pipe was not connected to the cars and the system was not charged.

Dynamic Brake

General Motors Model SD-40-2 dynamic brake system is established by placing the selector lever into Dynamic Brake Mode. This will convert the traction motors to generators to produce voltage and amperage which is dissipated in the form of heat through the braking grids. Excitation for the fields of the traction motors is developed through the main generator and is regulated by increasing main generator outputby increasing diesel engine rpm. This increase in engine rpm is accomplished by increasing throttle position 1 (setup) through 8 positions. The effectiveness of the dynamic brake system is generally maximized at speeds above 40 mph. At very speeds, below 10 mph, the dynamic brake system is not effective.

When the engineer failed to properly move the selector lever into the dynamic brake mode, the traction motors remained in the motoring mode. By placing the throttle handle into number 8 position in this set up, maximum locomotive power was thus developed and diesel engine rpm would increase in a like manner to dynamic braking. Without first observing the load meter, and at low locomotive speeds, it may be difficult to determine immediately if the locomotive was in braking or power mode.

Commentary

In the days following the incident, state and local officials expressed concern about the potential for this type of event to occur in the future. While FRA does not dismiss any potential safety concern, the exact circumstances that combined to cause this incident are highly unlikely to recur. It is not uncommon, today, for our inspectors to observe an engineer bring his locomotive to a full stop, dismount his locomotive and operate a switch. This is done safely and in accordance with railroad safety rules and does not pose any special hazard to employees or the general public. Railroad operating rules generally prohibit any employee from dismounting, or mounting, moving equipment. Engineers are required by railroad operating rules to apply a hand brake and take other steps at the control stand to immobilize the locomotive before dismounting.

FRA does have an initiative which will minimize the possibility of runaway equipment resulting from unsecured equipment left unattended in a yard. This issue falls under the umbrella of the Switching Operations Fatality Analysis (SOFA) program, in my view, and we have taken steps to emphasize the securement of equipment in our ongoing SOFA activities. For example, since the incident, State of Ohio and Federal inspectors have visited CSX and NS terminals in Ohio, and elsewhere, to review with railroad managers policies and procedures relating to switching safety, including securement. We have not been able to identify any systemic problems or shortcomings in training, supervision, or operating practices that are cause for alarm. Inspectors do observe various local, non-systemic safety issues, and they are addressed promptly with local managers, in accordance with our standard policy and practice.

I might comment further on why this incident is unlikely to recur. The cause of the incident was multiple gross errors in judgement by the locomotive engineer. For the incident to have occurred, each error needed to be committed in sequence. First, the engineer was not properly controlling the speed of his train on the lead, if he is unable to stop for a switch improperly lined. This is covered by the railroad's operating rules. Second, if the engineer cannot stop for a switch improperly lined, the correct action to take is simply run through the switch and then stop without backing up, to avoid derailing the train. Third, an engineer should never dismount his locomotive while it is moving, except in extremely rare emergency circumstances, such as an imminent collision. This is also covered by the railroad's operating rules. Fourth, the engineer should not have relied on dynamic braking at low speed, since dynamic brakes are ineffective at speeds of less than ten mph, except on an AC locomotive. This is well known among railroad engineers. Fifth, the engineer seemed to believe, in error, that an automatic brake application would improve braking power on single locomotive with the independent brake fully applied. Sixth, the engineer misapplied the selector handle for "power" or "dynamic brake," an error that can only be understood if we assume the engineer acted with extreme haste and negligence. That all of these actions were taken by an apparently well-qualified, fully rested employee with a good service record is simply incredible.

It should be remarked that this incident could only have occurred during freight car switching and not during passenger car switching. Most freight switching is done "without air," that is without air brakes functional in the train. This is the industry standard, and it has been so for many decades. Passenger switching, on the other hand, is usually performed "with air," that is with air brakes functional in the train. In addition, it should be noted that passenger coaches are rarely switched with passengers aboard, because of concerns with passenger safety. In those rare circumstances where passengers are on board during switching, the air brakes would always be fully functional.

Finally, this incident could not have occurred to either a passenger or freight train involved in over-the-road operations. Before any passenger or freight train embarks on a run outside of the yard where the train is assembled, federal regulations require that the train receive a thorough inspection of its braking system and that the brakes be 100% operational before the train is permitted to begin its journey.

Ссылка на источник: http://kohlin.com/CSX8888/z-final-report.htm

USA, Ohio

USA, Ohio